In the Veins of History

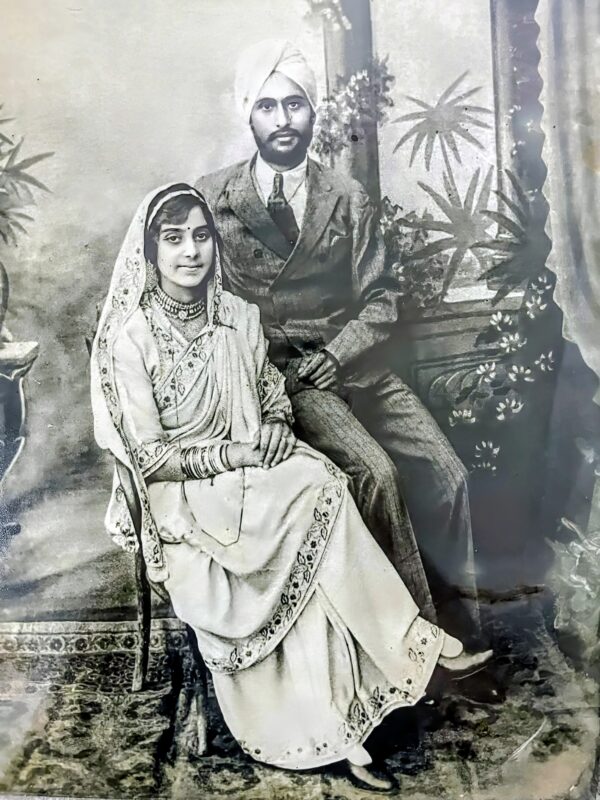

When I first turned the pages of The Punjab Chiefs, published in 1890 by Sir Lepel Griffin, I wasn’t just reading history — I was reading mine. In those firm colonial sentences was the unmistakable trace of my bloodline. Names I had heard in stories around a hearth now sat in stately print, their legacy inked by empire but lived far beyond it. This is the story — not just of my family — but of an enduring legacy of nobility, honor and unbroken cultural wealth.

The Punjab Chiefs: A Political Archive of Lineage, Allegiance, and Authority

In the aftermath of the British annexation of Punjab in 1849, the colonial state was not content with the sword alone. It needed documentation. The Punjab Chiefs, first compiled by Sir Lepel H. Griffin in 1865 under the title The Rajas of the Punjab, was a seminal British project aimed at identifying, categorizing, and aligning with the principal native aristocracy of Punjab.

The work recorded the genealogies, holdings, services rendered, and personal attributes of Punjab’s leading families — those who had governed under the Sikh Empire and now stood as potential allies or subjects under British rule. The first edition was followed by a major 1890 revision, and then brought up to date by Charles Francis Massy in subsequent decades. An Urdu translation of The Punjab Chiefs was also published.

“The actors in, and eye-witnesses of the events described have been questioned… their statements much new and interesting information has been gained.”

— Lepel H. Griffin, Introduction

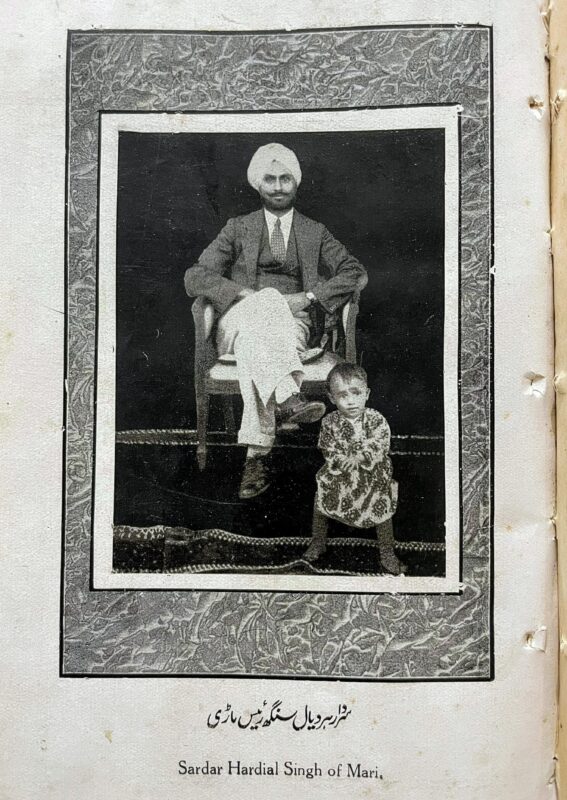

In being included in this register, a family was not merely described — it was institutionally recognized, politically trusted, and historically preserved. The House of Mari stands among those noble lineages.

The Mari Family: Shergill Nobility Rooted in Martial Tradition

Tribes, Villages, and the Durrani Invasion

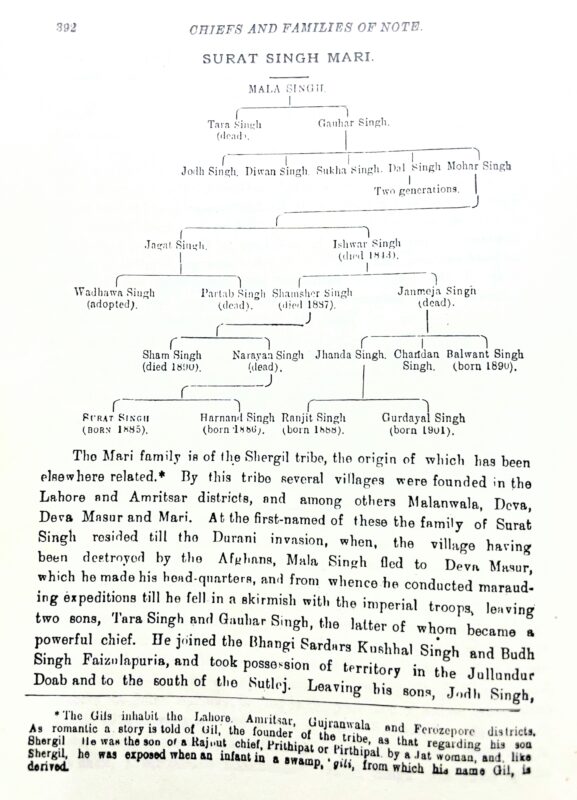

“The Mari family is of the Shergil tribe, the origin of which has been elsewhere related. By this tribe several villages were founded in the Lahore and Amritsar districts, and among others, Malanwala, Dewa, Dewa Masur and Mari.”

— The Punjab Chiefs, p. 392

Before British or Sikh governance, the Mari Sardars were landholding aristocracy. The patriarch Mala Singh, belonging to the Shergill tribe, resided in Malanwala until it was razed during the Afghan invasion. He fled to Dewa Masur and launched raids against the imperial troops until falling in battle.

He left behind two sons: Kaur Singh and Tara Singh.

“The former of whom became a powerful Chief. He joined the Bhangi Sardars Khushal Singh and Budh Singh Faizulapuria, and took possession of territory in the Jalandhar Doab and to the south of the Satlaj.”

— The Punjab Chiefs, p. 392

Kaur Singh returned to Mari and constructed a mud fort. The village came to be known as Mari Kaur Singhwala — a name that still endures.

As I walked through Mari as a child, I never realized how old the ground under my feet was — how it had held the weight of warhorses and treaties.

Defiance and Diplomacy

Siege by Maharaja Ranjit Singh and Treaty Terms

“When Ranjit Singh seized the country south of Lahore, the fort of Mari, then held by Mohar Singh, the youngest son of Kaur Singh, was besieged by him. Resistance was useless; and Mohar Singh gave up the fort and territory, obtaining favourable terms and large estates at Piru Chak, Bujbara, Samra and Manapur.”

— The Punjab Chiefs, p. 393

This was diplomatic survival — a negotiation that preserved dignity while shifting with the winds of sovereignty.

Service Under Arms

Mohar Singh, along with his brother Dal Singh, held jagirs under Ranjit Singh. Though initially exempt from service, the jagir was later subject to the maintenance of 100 horsemen.

“Mohar Singh served in the Kashmir Campaign, in which he was wounded. He distinguished himself at the battle of Teri in 1823, after which he was placed in command of five hundred cavalry.”

— The Punjab Chiefs, p. 393

He later fought under General Ventura in 1831 to annex Bahawalpur territory north of the Sutlej. General Jean-Baptiste Ventura had served in Napoleon’s Imperial Army, but after Napoleon’s abdication, Ventura was forced to flee the country and joined Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s Army.

Mohar Singh died the following year, and estates in Sialkot, Dinanagar, and Kasur were passed to his son Isar Singh, who served with distinction at Kulu, Suket, Hazara, and Peshawar before dying in 1843.

Resistance, Recompense, and Recorded Honor

Sardar Shamsher Singh and the 1848 Rebellion

“Shamsher Singh held the jagirs throughout the administration of Hira Singh, Jawahir Singh and Lal Singh. He accompanied Raja Sher Singh Atariwala to Multan in 1848, and rebelled with him.”

— The Punjab Chiefs, p. 394

Though young, Shamsher Singh wielded both ability and influence. After the rebellion, his jagirs — valued at ₹27,000 — were confiscated by the British. Yet his stature endured:

“In 1850 a pension of Rs. 720 was allowed him for life.”

— ibid.

He was later granted a rent-free estate worth ₹200 in 1860, along with proprietary rights in Mari Kaur Singhwala and Kazi Chak. Upon his death, he left behind two sons — Sham Singh and Narain Singh.

To his younger brother, Janmeja Singh, who had married Tej Kaur, daughter of Sardar Chatar Singh Atariwala (to whom Maharaja Dalip Singh had once been betrothed), a pension of ₹360 was granted.

“Gujjar Singh, Bhoop Singh and Kesar Singh, sons of Sardar Dal Singh, were cavalry officers under General Avitable… and the widows of Colonel Bhoop Singh draw an allowance of Rs. 720 from Government.”

— The Punjab Chiefs, p. 394

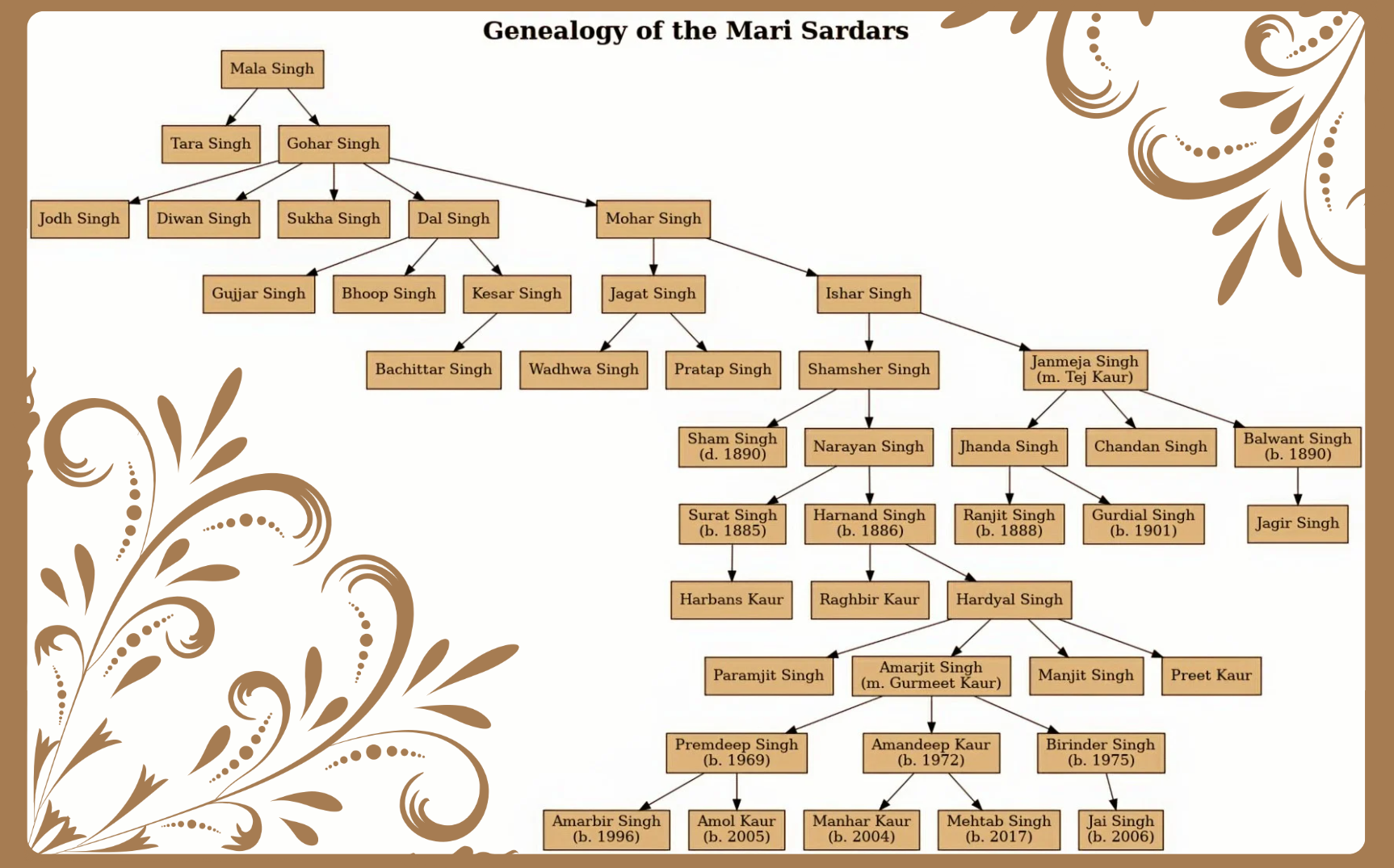

The Genealogical Line of the Sardars of Mari

The family tree, preserved both in colonial record and in internal family archives, is as follows:

A Living Legacy

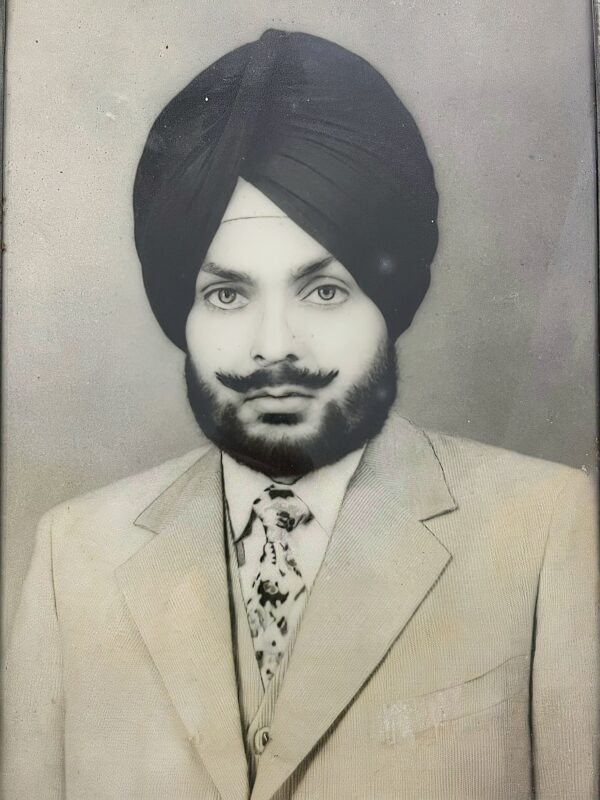

There are names that don’t fade with time — not because they seek attention, but because they are woven into the fabric of history.

The Sardars of Mari are one such name. Not exalted through ceremony or crowned in opulence, but recorded in ink, remembered in villages, and carried forward through generations who never allowed memory to wither.

From the ruins left by invasions to the margins of colonial registers, this lineage has endured — not by standing still, but by adapting with dignity. The men and women of this family did not chase legacy — they built it, moment by moment, in service, in silence, in strength.

To walk through Mari today is to walk through a landscape where history still breathes. In the names etched on old land records, in the stories proudly passed from one generation to the next, in the very air — there is continuity.

This is not a story of conquest.

It is a story of presence.

Uninterrupted. Rooted. Real.

And in that endurance, there is a kind of royalty that needs no title at all.

Sources:

- The Punjab Chiefs by Sir Lepel H. Griffin, Vol. I (1890), pp. 392–394

- The Sikh Encyclopedia – Punjab Chiefs

- JatChiefs.com – Mari

- Internal Family Tree: Sirdar Shamsher Singh Mari, 2024 Archive